Lisez-le en francais

Written by Aaron Mauro (PhD), Associate Professor Digital Media, Department of Digital Humanities at Brock University, Canada

Edited by Brittany Amell (PhD), Open Scholarship Policy Observatory, INKE, Electronic Textual Cultures (ETCL)

Available in PDF version here.

Summary

This short policy guide serves as an extension of the previous “Research Security and Open Social Scholarship in Canada” document published in 2023. This updated version addresses escalating threats to Canadian research ecosystems due to foreign espionage, geopolitical tensions (e.g., China, Russia), and politicization of academia.

The federal government has introduced stricter guidelines via the National Security Guidelines for Research Partnerships (NSGRP), a $12.6M-funded Research Security Centre, and tools like the six-page Risk Assessment Form to evaluate partnerships involving sensitive technologies (AI, quantum computing) or high-risk entities (sanctioned states, state-influenced institutions). Researchers must balance compliance with open collaboration while navigating uncertainties around dual-use technologies, foreign interference, and ideological pressures.

The U.S. context—marked by travel advisories for vulnerable researchers, militarized immigration enforcement (e.g., ICE’s expanded jurisdiction), and attacks on academic freedom—highlights vulnerabilities in the global knowledge economy. Canada seeks to mitigate risks through security reviews while preserving scholarly autonomy, but tensions persist between national security imperatives and democratic values like equity, inclusion, and free inquiry. As political polarization and AI-driven disinformation reshape research landscapes, universities face a critical challenge: safeguarding innovation without stifling international cooperation or academic freedom.

Table of Contents

PREAMBLE

The state of research security in Canada is governed by a few prevailing facts: Canada’s advanced technology, talent pool, and democracy make it a target for foreign espionage (criminal, nation-state, corporate). As such, the federal government and security services have raised concerns about threats to research integrity and national security, prompting new guidelines for protecting research and regulating foreign collaborations.

While these measures aim to safeguard sensitive information, they have created uncertainty among researchers about how to navigate international partnerships. The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated these concerns, prompting stricter guidelines and increased scrutiny of research projects. Universities are grappling with new rules regarding dual-use technologies (economic/military), critical infrastructure, and human-subject data research.

In what has been described as a “new era of research security,” researchers worry about maintaining academic freedom while adhering to national security directives, and some fear a return to McCarthy-era profiling based on nationality or ethnicity.[i] However, the new features of research security will continue to evolve rapidly alongside political polarization and the technological changes, such as LLMs and other AI tools, that serve to supercharge extremist disinformation online.

With multi-nation warfare raging in Palestine and Ukraine, increasing geopolitical tensions between major powers and trade wars represent the current drive to unwind post-World War globalization and peacekeeping efforts. Broader economic and national security threats posed by sole governing party of China (as well as those in North Korea, Iran, and Russia) increased awareness of the security of the Canadian research ecosystem.[ii]

As rules and guidelines become clearer, universities should aim to implement them without hindering high-quality scholarship or violating principles of equity and inclusion. This policy guide serves as an extension of the previous “Research Security and Open Social Scholarship in Canada” document published in 2023.[iii] This updated version will summarize the current threat model for researchers and the policy landscape required for security compliance.

THE RISKS OF FRIENDSHORING RESEARCH

Researchers must understand themselves as a feature and function of advanced economies, wherein research products drive economic growth and temper the social, cultural, and environmental consequences of progress.

The move to “nearshore” or “friendshore” economic relationships is driven directly by civil unrest in places like the Middle East, Ukraine-Russia, and the United States.[iv] In 2022, Janet Yellen coined the term “friendshoring” to describe a move to form economic supply chains within likeminded democracies.[v]

In what has now been defined as the (Cristia) Freeland Doctrine would limit trade with autocracies and encourage “in-between states” to embrace democratic values.[vi] In their evaluation of the so-called Freeland Doctrine, Kerry Buck and Michael Manulak that such an approach runs the risk of alienating nations and undermining global cooperation further:

With the world headed, perhaps inevitably, toward increasing strategic competition, Freeland’s vision could be easily interpretated in a manner that risks exacerbating polarization, undercutting multilateral organizations and international rules.[vii]

Universities are multilateral organizations that cooperate to innovate, create, and critique in a collaborative, open, and social way. Breaking international cooperation with research universities and other academic partnerships runs the risk of entrenching autocratic power because, as Peter Beinart explained in 2018, sanctions “erode the habits and capacities necessary to sustain liberal democracy over the long term.”[viii] While many educational jurisdictions face government interference on ideological and economic grounds, Canadian researchers face unique exposure to ideological attacks on institutions of higher education in the United States.

The security situation in the United States continues to evolve. The April 15th, 2025 announcement from the Canadian Association of University Teachers, advised against non-essential travel to the US. Additionally, the CAUT warned “particular caution” for anyone falling into the following categories:

- Citizens or residents of a country identified in media reports as likely to be subject to a travel ban

- Citizens or residents of a country where there are diplomatic tensions with the U.S.

- Travellers with passport stamps evidencing recent travel to countries that may be subject to a travel ban or where there are diplomatic tensions with the U.S.

- Those who have expressed negative opinions about the current U.S. administration or its policies (I love this one)

- Those whose research could be seen as being at odds with the position of the current U.S. administration

- Travellers who are transgender or whose travel documents indicate a sex other than their sex assigned at birth[ix]

This warning came as a sobering reminder of the vulnerability of knowledge workers in the knowledge economy in the face of political change. However, Canada is not immune to such forces. Alex Usher describes the challenges of politicization of universities. While places like China and Russia “tighten their grip on higher education—not because of polarization, but because they see academia as a threat.” Usher reminds us that Canada is not immune to these forces, wherein Ontario performatively defends free speech for right wing commentors[x] and Alberta agitates for shutting down equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) programs in universities[xi]: “We’re not insulated from it,” Usher explains, “but the pressures here are less extreme” than in sole governing autocratic countries.[xii]

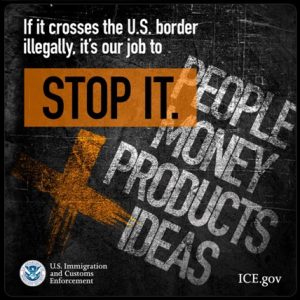

ICE ad posted on X, formerly Twitter (2025)

Knowledge and knowledge workers can be regulated and limited by law enforcement agencies. As researchers seek to collaborate with US-based counterparts, sensitive ideas may come under the scrutiny of US law enforcement or military agencies.

This context explains Canada’s place in the global market for ideas, but it also serves as a moment to bear witness in the face of rapid political, economic, and ideological change. In keeping with these changes, the United States Government has been deleting public records that do not conform to its vision of the country since the 2024 Presidential election.[xiii]

The security of research and researchers is a critical question today, as US Marines and National Guard are deployed in Los Angeles against American citizens.[xiv] The Marines and National Guard are presumably deployed to protect Immigration Customs Enforcement (ICE) officers to apprehend illegal immigrants, yet the current ICE administration includes “people, money, products” as well as “ideas” within its jurisdiction, as was presented on an advertisement on X, formerly Twitter, in April of this year.[xv] Academics should listen to what they are being told by the US administration.

Knowledge and knowledge workers can be regulated and limited by law enforcement agencies. As researchers seek to collaborate with US-based counterparts, sensitive ideas may come under the scrutiny of US law enforcement or military agencies.

PROTECTING PEOPLE, IDEAS, AND INFRASTRUCTURE

At this moment, it is important to note that academic exchanges differ from economic exchanges. The US remains a central engine of scholarship globally, despite recent attacks on its most prestigious and productive institutions like Columbia and Harvard. The so-called “Letter Sent to Harvard” is a clear statement of the current US administration’s goals for higher education and the whole of the research enterprise in the country, centred around “viewpoint diversity.”[xvi]

As little more than a dog whistle for the far-right ideological engineering of higher education, “viewpoint diversity” seeks to erase generations of research and scholarship predicated on the post-World War foundation that harm reduction, cross-cultural understanding, and compassion are the basis of a stable and peaceful society. If Canadian researchers do not engage with US centres for excellence at this moment, there is a risk of isolating colleagues when they most need our support in maintaining the habits and capacities necessary to sustain a scholarly tradition over the long term.

If security culture functions as an “expression of values,” those values must also reflect our shared commitment to open and social scholarship.[xvii] The merit of data, ideas, and arguments will be validated and supported through peer review, utility, and economic value. Who and what we value can be expressed by how we offer those people and things security.

The Canadian government allocated $12.6 million over five years (plus $2.9M ongoing) in 2022’s budget to establish the Research Security Centre under Public Safety Canada, aiming to protect national research through security reviews, policy guidance, and collaboration with academic institutions. The Research Security Centre operates a nationwide network of six regional advisors covering all provinces and territories, supported by a central hub in Ottawa, to provide localized support and expertise on sensitive technology research and affiliations of concern. It fosters a secure innovation environment by offering workshops, technical advice, access to federal services, and promoting a balance between open academic collaboration and safeguarding against illicit knowledge transfers.[xviii]

Canada’s framework for managing national security risks in international or domestic research collaborations has been defined in The National Security Guidelines for Research Partnerships (NSGRP), introduced in 2021 by the Canadian government.[xix] The NSGRP seeks to balance open research collaboration with national security safeguards. It emphasizes adherence to legal requirements such as the Export Control List (ECL) under the Export and Import Permits Act (EIPA), which governs sensitive areas like nuclear, chemical, biological, radiological, and space technologies.

High-risk partnerships—those involving sanctioned entities, countries on Canada’s Area Control List, or dual-use research with potential military applications—are subject to stricter oversight, including mandatory export permits and authorization from government bodies like Global Affairs Canada. Emerging “dual-use” technologies (with unclear civilian/military distinctions) are flagged as sensitive, requiring researchers to stay informed about evolving regulatory updates.

While the NSGRP speaks to how “international partnerships are an essential component of Canada’s open and collaborative academic research,” these guidelines also stress the importance of assessing partner-related risks, such as state-owned or state-influenced entities that may prioritize ideological objectives of a government over open research and discovery. Institutions lacking autonomy pose greater risks due to potential compliance with foreign legal mandates compelling knowledge transfer.

Researchers are advised to evaluate collaborators’ ties to foreign governments, militaries, or intelligence agencies and address conflicts of interest. The NSGRP highlights the role of Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) and cybersecurity assessments in identifying global threats, while emphasizing that these guidelines apply broadly rather than targeting specific countries. Compliance with legal frameworks like the Defence Production Act and Controlled Goods Program is critical to mitigating risks linked to knowledge theft or unauthorized technology dissemination.

RESEARCH RISK ASSESSMENT

The NSGRP serves as a primer for the “Risk Assessment Form,” a six page, form fillable PDF separated into five sections.[xx] This Risk Assessment Form is a tool designed to evaluate national security risks associated with research partnerships as outlined in Canada’s National Security Guidelines. This form is a starting point to assess sensitive research and assist members in the Canadian security establishment to evaluate relative risk related to research. It requires applicants to provide detailed information about their proposed research area and partner organizations to identify potential vulnerabilities such as foreign interference, espionage, or intellectual property theft.

The form defines “partner organizations” broadly, including entities that contribute financially, share expertise, participate in research activities, or help translate findings into outcomes. Risks are assessed based on whether partnerships could advance hostile states’ capabilities (e.g., military or intelligence) or undermine Canadian critical infrastructure and sensitive data protection. Importantly, the form is not used to verify compliance with legal requirements but rather to gauge the overall risk profile of a project.

The Risk Assessment Form is available online.

“By completing the form, users help ensure that collaborative research does not inadvertently expose projects—or Canada’s broader innovation ecosystem—to threats like unauthorized knowledge transfer or interference by foreign actors.”

The Risk Assessment Form emphasizes due diligence for all stakeholders engaging in national, international, or multinational partnerships. It applies to any individual or institution administering grants and encourages proactive risk mitigation strategies. By completing the form, users help ensure that collaborative research does not inadvertently expose projects—or Canada’s broader innovation ecosystem—to threats like unauthorized knowledge transfer or interference by foreign actors. The collected information is strictly used for internal risk evaluation, focusing on balancing international collaboration with national security imperatives.

Open-Source Intelligence (OSINT) gathering is a process wherein a researcher can collect as much public data as possible to make determinations about the credibility and risk associated with a research organization. The Conducting Open Source Due Diligence for Safeguarding Research Partnerships document provides a comprehensive guide on conducting OSINT due diligence to safeguard research partnerships, emphasizing methods to identify, assess, and mitigate risks through publicly available information.[xxi] It outlines tools for corporate records (e.g., SEDAR, EDGAR, Open Corporates),[xxii] many of which are free, to verify partner organizations’ legitimacy and ownership structures globally.

The guide stresses systematic approaches: using controls to refine search results, making evidence-based decisions, documenting findings clearly to communicate risks effectively, and avoiding speculation by anchoring conclusions in verified data. It also highlights the importance of logical risk assessment frameworks (e.g., “panel thought experiments”) and emphasizes that due diligence is iterative, requiring thorough documentation for accountability and future reference. Targeting researchers, administrators, and technology transfer professionals, the guide aligns with Canada’s efforts to protect intellectual property and research agendas in collaborative partnerships while balancing transparency and national security considerations.

NSGRP guidelines apply to selected federal research partnership funding programs involving private sector partners under agencies like NSERC, CIHR, and SSHRC. Applicants must submit a Risk Assessment Form evaluating risks tied to their research area (e.g., sensitive technologies) and partner organizations (including industry groups or consortia), along with a tailored risk mitigation plan. Granting agencies review these assessments internally using open-source intelligence, referring high-risk cases to Public Safety Canada’s Research Security Centre for further evaluation.

If national security concerns arise, funding decisions may be delayed by up to 10 weeks and mitigation measures become mandatory. The NSGRP emphasizes non-discrimination in risk assessments and complements the Policy on Sensitive Technology Research and Affiliations of Concern (STRAC), which addresses risks from affiliations with high-risk research organizations.

Resources for due diligence are available via the Safeguarding Your Research portal, while annual reports track NSGRP implementation outcomes. Applicants must confirm mitigation plan compliance during grant reporting, and conditional funding may require post-assessment meetings to address security concerns.[xxiii]

OPEN-SOURCE INTELLIGENCE GATHERING AND COLLABORATION

In section 1, the Risk Assessment Form captures research within the following sectors: energy and utilities, water, finance, safety, food, manufacturing, transportation, information and communication technology, government, and health. This general sector identification is augmented by the list of “sensitive technology research areas,” which includes advanced manufacturing, artificial intelligence, quantum computing, and other technologies.[xxiv]

The sectors account for broad swaths of the university research activity in Canada. Additionally, those working with personal data, which information relating to the following: age; culture; disability; education; ethnicity; gender expression and gender identity; immigration and newcomer status; Indigenous identity; language; neurodiversity; parental status/responsibility; place of origin; religion; race; sexual orientation; socio-economic status; blood type; fingerprints; medical, criminal or employment history; financial transactions; and home address.

Many researchers working in Canada with international partners can be implicated in this approach. Section 2 requires researchers to “know your partner organization.” This is places the responsibility to “assess whether your partner organization(s) could pose a national security risk.” The means and measures of this assessment are not stated, but there is a list of research institutions with whom research “will not be funded.”[xxv] There are 8 research institutions in Russia and 98 research institutions in China on this list.

“The Risk Assessment Form asks, ‘Are there any indicators that your partner organization(s) could be subject to foreign government influence, interference or control?’ If researchers are working with colleagues at Harvard or Columbia, Canadian researchers would be compelled to select, ‘Yes,’ assuming they have been following the news and reading discretely shared PDF documents released by the Harvard administration. Of course, various Canadian jurisdictions, such as Ontario and Alberta, could also be determined to subject researchers to government influence, interference or control.”

The Risk Assessment Form asks, “Are there any indicators that your partner organization(s) could be subject to foreign government influence, interference or control?” If researchers are working with colleagues at Harvard or Columbia, Canadian researchers would be compelled to select, “Yes,” assuming they have been following the news and reading discretely shared PDF documents released by the Harvard administration. Of course, various Canadian jurisdictions, such as Ontario and Alberta, could also be determined to subject researchers to government influence, interference or control.

Identifying risks in section 3 thereby assumes that researchers are able to know a risk when they see it. With a 4,800 word limit, researchers must account for the risks to national security their international collaborations pose. “Raising research security awareness and building capacity across your research team” also adds a significant burden for researchers. A team within the INKE Partnership is currently developing the Research and Information Security Kit (RISK) to address this gap in support for capacity building within research teams.[xxvi]

Canada’s research security landscape is shaped by growing threats from foreign espionage, geopolitical tensions, and the politicization of academia, driven by its advanced technology sector and democratic values.

The federal government has introduced stricter guidelines to protect sensitive research and regulate international collaborations, particularly with nations like China, Russia, and Iran, amid concerns about dual-use technologies and national security risks. However, these measures have created uncertainty for researchers navigating global partnerships while safeguarding academic freedom. U.S.-Canada tensions, including travel advisories for vulnerable researchers and the militarization of immigration enforcement, highlight vulnerabilities in the knowledge economy, where ideas themselves may face regulatory or ideological control under shifting political climates.

To address these challenges, Canada has established frameworks like the NSGRP and a $12.6M-funded Research Security Centre to mitigate risks from foreign interference, intellectual property theft, and unauthorized technology transfers. The guidelines emphasize due diligence in partnerships, requiring researchers to assess potential security risks. Researchers mush assess ties to state-controlled institutions, especially in the case of dual-use technologies through tools like the six-page Risk Assessment Form.

This form evaluates collaborations based on sectors (e.g., AI, quantum computing) and partner organizations’ susceptibility to foreign influence. While Canada aims to foster secure innovation without stifling academic collaboration, researchers face added burdens in understanding evolving regulations and ensuring compliance with legal frameworks. Balancing open scholarship with security remains a core challenge as global instability reshapes research ecosystems, demanding vigilance against both external threats and internal politicization of universities.

FURTHER RESOURCES

- General Information on Research Security : https://science.gc.ca/site/science/en/safeguarding-your-research/general-information-research-security.

- Guidelines and Tools to Implement Research Security: https://science.gc.ca/site/science/en/safeguarding-your-research/guidelines-and-tools-implement-research-security.

- National Security Guidelines for Research Partnerships: https://science.gc.ca/site/science/en/safeguarding-your-research/guidelines-and-tools-implement-research-security/national-security-guidelines-research-partnerships

ENDNOTES

[i] Brian Owens, “A New Era of Research Security,” University Affairs / Affaires Universitaires, 14 June 2023: https://universityaffairs.ca/features/a-new-era-of-research-security/.

[ii] Government of Canada, “China’s Intelligence Law and the Country’s Future Intelligence Competitions,” Canadian Security Intelligence Service, 17 May 2018: https://www.canada.ca/en/security-intelligence-service/corporate/publications/china-and-the-age-of-strategic-rivalry/chinas-intelligence-law-and-the-countrys-future-intelligence-competitions.html.

[iii] Caroline Winter, “Research Security and Open Scholarship in Canada,” Open Scholarship Policy Observatory, 17 November 2023: https://doi.org/10.25547/X9Z8-SZ32.

[iv] Olivia Dobson and Patrick Roberts, “Rising Political Risks Overshadow ‘friendshoring’ Shift,” 18 January 2024: https://www.maplecroft.com/products-and-solutions/sustainable-supply-chain/insights/rising-political-risks-overshadow-friendshoring-shift/.

[v] Atlantic Council, “Janet Yellen on the next steps for Russia Sanctions and ‘friend-shoring’ Supply Chains,” 13 April 2022: https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/news/transcripts/transcript-us-treasury-secretary-janet-yellen-on-the-next-steps-for-russia-sanctions-and-friend-shoring-supply-chains/.

[vi] Kerry Buck and Michael W. Manulak, “Friend-Shoring Canada’s Foreign Policy?” Policy: Canadian Politics and Public Policy, 29 October 2022: https://www.policymagazine.ca/friend-shoring-canadas-foreign-policy/.

[vii] Ibid.

[viii] Peter Beinart, “How Sanctions Feed Authoritarianism,” The Atlantic, 5 June 2018: https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2018/06/iran-sanctions-nuclear/562043/.

[ix] Canadian Association of University Teachers, “2025 Supplement to the CAUT Advisory on Travel to the United States,” Briefing Note, 15 April 2025: https://www.caut.ca/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/caut-2025-Supplement-to-the-CAUT-Advisory-on-Travel-to-the-United-States-2025-04.pdf.

[x] James L. Turk “A Manufactured Crisis: the Ford Government’s Troubling Free Speech Mandate,” Academic Matters: OCUFA’s Journal of Higher Education, 2018: https://academicmatters.ca/a-manufactured-crisis-the-ford-governments-troubling-free-speech-mandate/.

[xi] Hannah Liddle, “Insight the University of Alberta’s Move Away from Equity, Diversity and Inclusion,” University Affairs / Affaires Universitaires, 28 January 2025: https://universityaffairs.ca/news/inside-the-university-of-albertas-move-away-from-equity-diversity-and-inclusion/

[xii] Alex Usher, “Where Canada Lies in Global Trends with Alex Usher,” The World of Higher Education Podcast, 9 January 2025: https://higheredstrategy.com/where-canada-lies-in-global-trends-with-alex-usher/.

[xiii] Rachel Santarsiero (ed), “Disappearing Data: Trump Administration Removing Climate Information from Government Websites,” National Security Archive, 6 February 2025: https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/briefing-book/climate-change-transparency-project-foia/2025-02-06/disappearing-data-trump; and Kathryn Palmer, “Preserving the Federal Data Trump Is Trying to Purge,” Inside Higher Ed, 10 June 2025: https://www.insidehighered.com/news/government/science-research-policy/2025/06/10/preserving-federal-data-trump-trying-purge.

[xiv] Eleanor Watson, “700 Marines Arrive in L.A. area Amid ICE Protests as Newsom Files Suit to Block Deployment,” CBS News, 10 June 2025: https://www.cbsnews.com/news/marines-high-alert-deploy-los-angeles-ice-protests/.

[xv] Ali Bianco, “ICE says its job is to stop illegal ‘ideas’ crossing the border in since-deleted X post,” Politico, 10 April 2025: https://www.politico.com/news/2025/04/10/ice-speech-censorship-007886.

[xvi] Josh Gruenbaum, Sean R. Keveney, and Thomas E. Wheeler, “Letter to Alan M. Garber: President of Harvard University.” 11 April 2025: https://www.harvard.edu/research-funding/wp-content/uploads/sites/16/2025/04/Letter-Sent-to-Harvard-2025-04-11.pdf

[xvii] Aaron Mauro, “Security Culture as an Expression of Values,” Pop! No. 5 (2023). https://doi.org/10.54590/pop.2023.003

[xviii] Government of Canada. “About the Research Security Centre,” 9 April 2024: https://www.canada.ca/en/services/defence/researchsecurity/about.html.

[xix] Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, “National Security Guidelines for Research Partnerships,” Science.gc.ca, January 2024: https://science.gc.ca/site/science/en/safeguarding-your-research/guidelines-and-tools-implement-research-security/national-security-guidelines-research-partnerships#1. See also: https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/trnsprnc/brfng-mtrls/prlmntry-bndrs/20240813/03-en.aspx.

[xx] See https://science.gc.ca/site/science/sites/default/files/attachments/2023/risk_assessment_form_ISED-ISDE3832E.pdf.

[xxi] Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, “Conducting Open Source Due Diligence for Safeguarding Research Partnerships,” Science.gc.ca, January 2022: https://science.gc.ca/site/science/en/safeguarding-your-research/guidelines-and-tools-implement-research-security/guidance-conducting-open-source-due-diligence/conducting-open-source-due-diligence-safeguarding-research-partnerships.

[xxii] Respectively, SEDAR (System for Electronic Document Analysis and Retrieval) is offered by the Canadian Securities Administrators (CSA); EDGAR (Electronic Data Gathering, Analysis, and Retrieval) is offered by the United States Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC); OpenCorporates is a Certified B Corp providing reliable data on registered corporations globally.

[xxiii] See “Tri-agency guidance on the National Security Guidelines for Research Partnerships (NSGRP): https://www.nserc-crsng.gc.ca/InterAgency-Interorganismes/RS-SR/nsgrp-ldsnpr_eng.asp

[xxiv] See https://science.gc.ca/site/science/en/safeguarding-your-research/guidelines-and-tools-implement-research-security/sensitive-technology-research-and-affiliations-concern/sensitive-technology-research-areas.

[xxv] See https://science.gc.ca/site/science/sites/default/files/documents/2024-01/1082-named-research-organizations-list-09Jan2024.pdf.

[xxvi] See Research and Information Security Kit: https://www.researchsecuritypolicy.com/.